Recently, I came across a dated document on Uranium City in my extensive files. There was no author. So I simply referenced it as “document” and I give credit to the anonymous writer, whoever he, or she, is. Strangely enough, there was scant data on Uranium City. But I did come across a booklet titled The history of Uranium City and Districtauthored by a class of Grade 10 high school students from Uranium City. Good work. Which means they had a great teacher

I think it likely that a fair number of citizens in the Battlefords worked in Uranium City during their younger years.

Geography

Uranium City is situated on the north shore of Lake Athabasca – about 400 miles from Prince Albert and an equal distance from Edmonton. The community is situated in Saskatchewan about 70 miles from the Alberta border. The boundary of the municipality lies between Tazin Lake and River on the north and extends 10 miles into Lake Athabasca on the south. On its western side, its boundary is situated near Camsell Portage and, to the east, it is encompassed by Old Man River.

Lake Athabasca was an old high road in the fur trade that extended into the 18th and 19th centuries. Alexander MacKenzie travelled down Lake Athabasca on his journey north. The site was discovered in 1949 by S. Kaiman who was researching radioactive materials around Lake Athabasca. Outside of trapping and prospecting, there was little activity in the region until gold was discovered in the late 1930s. The goldfields operated until World War II broke out. When uranium was discovered in the early 50s, the population of Uranium City exploded (reminiscent of the 1998 Klondike gold rush.) The population was mainly transient during the early years, and for a time, Uranium City resembled the wild west. There were some wild times indeed.

The goldfields

In August of 1934, gold was discovered on Lodge Bay on Lake Athabasca by G. Nieman and Tom Box. Ore samples contained, not only gold, but nickel, copper, molybdenum and lead and silver. It was a bonanza. Mining companies and independent prospectors rushed to Lodge Bay. By 1937, 2000 miners had taken up residence. The major player in the mining enterprise was Consolidated Mining and Smelting of Canada. The first gold brick was poured in August of 1939. It weighed 75 and one-half pounds and was valued at $30,000. What would it be worth today?

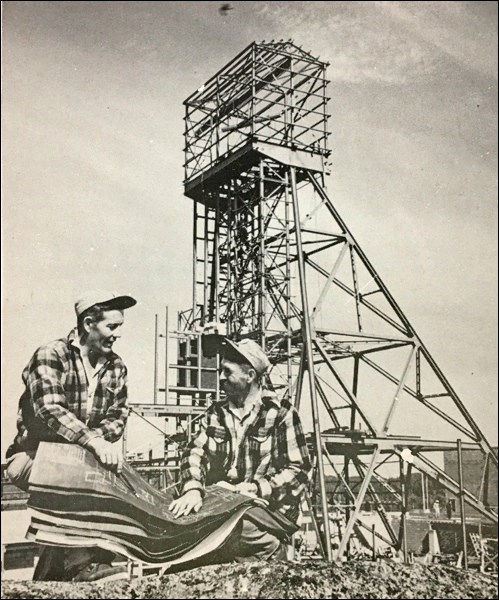

Eldorado

The largest operation in Uranium City was Eldorado Nuclear Limited. Previously, it was referred to as Eldorado Mining and Refining Limited. There were a number of smaller mines in operation as well but the other major player in the uranium business was Lorado Uranium mines.

Eldorado Gold Mines Ltd. mined gold in the Long Lake District of northern Manitoba until the gold deposits were depleted. So the mine’s directors decided to invest in exploration in other areas. In 1929, Gilbert Labine, managing director and an experienced prospector, flew to Great Bear Lake, North West Territories, and staked a claim at Hunter Bay. On the way back he noticed a cobalt bloom on the cliffs. It was 30 miles south of his claim so he decided to return the following year. He found a high grade of silver and pitchblende. This was the start of Eldorado Nuclear.

A single gram of radium was worth $70,000 in 1930. What would a gram of radium be worth in today’s dollars? During the early years, radium was used for cancer treatment. Later it was used for military purposes – atomic bombs and weapons of mass destruction. These doomsday weapons did not appear to influence anyone’s sense of morality.

Mining uranium was extremely difficult. To produce one gram of radium, it was necessary to extract 500 tons of ore, which had to be reduced to 10 tons of concentrate, which was about 60 per cent uranium oxide. The next step was to turn the uranium oxide into uranium. Seven tons of chemicals were required.

World War II changed the views of a majority of citizens worldwide who condemned the military use of uranium. Eldorado was forced to close its mine in 1940. But then the Manhatten Project (the production of atomic bombs to be used in the Pacific Theatre of the World War II) resurrected Eldorado Nuclear. In 1944, the federal government expropriated Eldorado Nuclear, making it a crown corporation. In 1946, Eldorado developed a Cobalt-60 beam therapy for cancer – the first of its kind and an extraordinary achievement. The company’s fortunes looked bright. Explorations in the Lake Athabasca area led to the discovery of a large ore body near Fish Hook Bay, the Fay Ore body, and Ace Lake. The province was pressured to subdivide the area into 25-mile claims. In 1954, 14,000 claims were staked. It was necessary to impose law and order.

Despite Eldorado’s pioneering spirit, willingness to innovate and change direction, marketing genius, and many successes, its fortunes slowly declined. The primary reason was that uranium sales dictated an uncertain market. Eldorado could not rely on unstable world politics. (Yet despite these obstacles, Eldorado would have one more opportunity for success decades down the line.) During the prosperous years, uranium was in demand for defence purposes, but when the company’s buyers had stockpiled all the uranium they needed, prices declined steeply and a once thriving community became poor. Residents left in droves except for the diehards who stayed on.

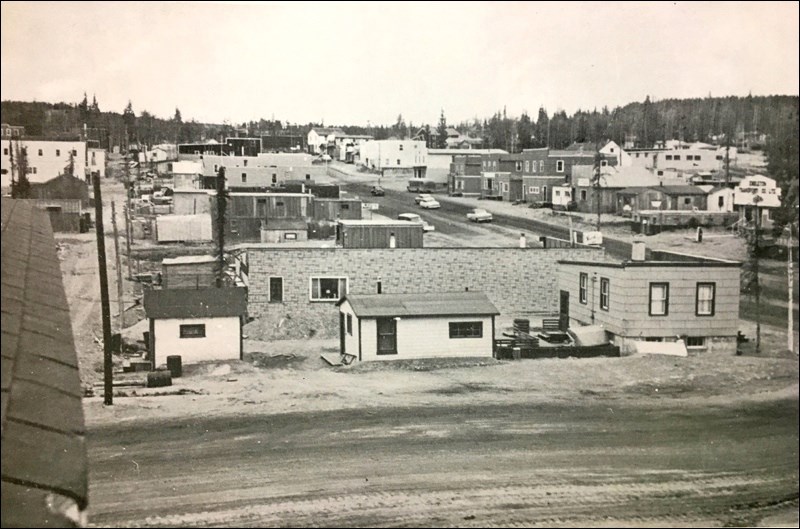

In 1956, Uranium City had a population of about 1,800 with another 2,200 in the surrounding district. Provincial authorities decided that the local government should assume the county form, the only county in Saskatchewan. Education and hospitals became the responsibility of the Uranium City Municipal Council.

Population reached a peak of 4,600 in 1959. In 1960, Lorado, who was in partnership with Eldorado Mining, and who had a contract with the American government, sold its contract and went out of business. Smaller mines had to follow suit. The collapse resulted in a near panic. The population dropped from 2,500 to 1,650 and continued its downhill slide to 1,450 persons.

During the explosive growth of Uranium City in the boom years, a great deal of substandard housing was constructed. After the collapse, a large number of houses became vacant and a substantial number of these were vandalized. The local government took over 177 houses, of which only 48 were marketable.

As mentioned, Uranium City is about 400 miles from both Edmonton and Prince Albert. The landscape between these two cities is extremely rugged. The cost of constructing a road to Uranium City would have been enormous. Authorities worked on the practicality of constructing a road from north of Fort McMurray, or Fort Smith. Heavy freight was transported by barge from waterways down the Athabasca River and up Lake Athabasca. The only other transportation was by air. The community was serviced by Norcanair operating out of Prince Albert and Pacific Western Airlines operating out of Edmonton. Eldorado Nuclear had its own private air service.

Despite the failure of Uranium’s economy in 1960 (because once military quotas have been met, nations have no further need for uranium), the potential for a bright future came into focus once again, and rather quickly. Uranium had immense value as a fuel for nuclear power plants. At that time, nuclear power stations competed with hydro and fossil fuels but that was certain to change. In the meantime, it would take a long time to build a power plant in a highly populated area. It was expected there would be a strong surge in uranium sales in the early seventies.

Prospecting suddenly became intense in response to this future market. Eldorado Nuclear began developing a new mine known as Hab and began stockpiling uranium against the future market. As a result, the population increased to 2,650 people. The boom days were, of course, very exciting. But the steady growth was far better in terms of community planning and stability. Things were looking up. But not forever. Nations stockpiled uranium for military purposes and governments stockpiled for nuclear power plants. The writing was on the wall.

Community

Uranium City was fortunate to have excellent medical and educational facilities – as good as any in the outside world. This assisted in making the community an attractive and healthy place in which to raise a family.

As a recreational area, Uranium City and the area surrounding it, was unsurpassed. Here, nature could be found in its original state. Lakes are abundant in pickerel, trout and grayling. At that time, a number of fishing camps catered to American fishermen.

The community itself boasted a hockey and curling arena, theatre, kiddie’s playground, and three churches. Eldorado Nuclear boasted a gymnasium, bowling alley, pool room, curling arena, picture house, restaurant, squash court and boating marina. Add this to top wages, and one understands why workers came to Uranium City for the long haul.

Uranium City has had telephone communication with the outside world since 1962. It also had a local radio transmitter that repeated a program originating in Yellowknife and which was brought in over the telephone lines. Some southern programs were also brought in over this radio link. Television – “frontier package”– reached Uranium City in 1968. It provided residents with television programming for four hours a day. This was a very welcome diversion during the bitterly cold months.

Unfortunately, development and good times did not last. In 1982, Uranium City was a thriving community of 2,500 people. Infrastructure was planned to accommodate a population of 5,000. Then the closure of the mines led to an economic collapse. Most of the residents left. About 200 stayed, and these included a number of Métis and First Nations people. Uranium City and surrounding districts took on the character of a ghost town

In June of 2016, Uranium City with the First Nations of Hatchet Lake, Fond du Lac and Black Lake, and the communities of Camsell Portage, Wollaston Lake and Stony Rapids collaborated to sign a historic agreement with Cameco and Orano (formerly AREVA Resources). It was designed to enhance and support a workforce and business development, environmental stewardship and community investment in the Athabasca station. The Joint Implementation Committee tabled a 2017 Report to Community Members which detailed progress made until yearend.

The history of Uranium City is one of contrasts. There were good times and bad times. There was prosperity and there was poverty. There was a building boom, followed by many structures falling into disrepair. In the larger view, Uranium City had been an ideal place to live and work for extended periods of time, and residents who departed must have left with good memories. And Eldorado Nuclear, while it was in operation, was an economic powerhouse employing hundreds of workers.

(Sources: Uranium City, Saskatchewan, Anonymous flyer, n. d.; A history of Uranium City and District, Grant Dougill, 1982; Internet)